You’ve heard it said–maybe you yourself have said it:

“There’s no point to character alignments in D&D or any other roleplaying game. It’s an unnecessary hindrance to players!”

Or if you’re a proponent of alignments, you’ve seen the eye-rolls from players and other GMs. I mean, who really takes those kinds of rules seriously? Should alignments even exist in roleplaying games?

Well, I am taking those rules seriously, as I play my way through First Edition AD&D. And I’m not simply finding them tolerable, I’m actually really enjoying the rules on alignment.

As someone who played 4th Edition D&D consistently for about four years (and has even dabbled a bit in the last year, believe it or not), I’ve experienced the other side of alignments. In the 4e Essentials book, Heroes of the Forgotten Kingdoms, alignment is discussed in this way:

“A character’s alignment describes his or her moral stance. Many adventurers…are unaligned, which means they have no overriding moral stance. … Most people in the world, and plenty of adventurers, haven’t signed up to play on any team–they’re unaligned. Picking and adhering to an alignment represents a distinct choice.

If you choose an alignment for your character, you should pick either good or lawful good” (Mearls, Slavicsek, and Thompson, pg. 43).

As I’ve played 4th Edition, my experience has been that 4e alignment rules functionally led to no alignments at all. Which is fine! I just think it’s an unfortunate drift from their original function. So why were alignments originally written into D&D? And how can their rigorous use actually benefit our games?

Alignment began as an essential part of character creation

While 4e dismisses alignments as the personal choice of a few, this was not the case in earlier editions. OD&D contained alignments in an early protoplasmic form called “stances” that reflected Law, Chaos, and Neutrality. D&D Basic added the language of “alignments,” the Good-to-Evil spectrum, and this note:

“If the Dungeon Master feels that a character has begun to behave in a manner inconsistent with his declared alignment he may rule that he or she has changed alignment and penalize the character with a loss of experience points. An example…would be a ‘good’ character who kills or tortures a prisoner” (Holmes, pg. 8).

Now alignment has some teeth. But D&D Basic doesn’t really justify penalizing players for violating their alignment. Why does it matter? What is unclear in Basic becomes crystal clear in AD&D: alignments are meant to give characters meaningful depth, both in terms of their ethics and their personality.

Thus, in AD&D, you choose your character’s alignment before you choose your equipment. It’s right after their class. It’s not an appendix! It’s not a sidebar. It’s right there in the middle. Why? Gygax tells us in the DMG:

“…alignment describes the world view of creatures and helps to define what their actions, reactions, and purposes will be. It likewise…aids players in the definition and role approach of their respective game personae” (pg. 23).

Alignment restricts players to help them

Does alignment restrict players? Yes. Most certainly. That’s the intention! But why? It’s because restriction forces people to make hard choices. And one of the great thrills of roleplaying is facing difficult challenges and making hard choices.

Let’s look at it from the other end of the spectrum. In the last 4e campaign I played in (last year), our party of three players had, by the end of the campaign, devolved into the most heinously inhuman murder squad I’ve ever witnessed. Enemies, NPCs, buildings–didn’t matter. If we didn’t trust it, it died. And I can promise you this: none of us had a clue what our alignment was. It didn’t matter, because there were no clear ramifications for acting outside of alignment.

Now, let’s fast forward to 2017: AD&D. So our party of six is in the village of Orlane, investigating a case of a missing person. While we do have an evil character in the party, we also have three rangers, which means three good-aligned characters. The PCs are so close to the truth behind the façade, it’s starting to drive them nutty. So in a moment of passion, one of our rangers notched an arrow to take out a prisoner. Enter, me, the GM:

“As a player, you’re welcome to do what you want. But remember that this will threaten not only your status as a ‘good’ character, but also as a ‘ranger.’ Consider carefully what your character would do.”

It might seem like a jerky thing for me to do. I mean, isn’t roleplaying all about freedom of choice? Not according to the July 1981 issue of Dragon Magazine. In it Roger Moore reflects on the difficulty of playing a paladin. Not only did the necessary restrictions on the class “give it a wealth of special problems in play,” but it was a class that he rarely saw “done at least reasonably right most of the time.” In the end, he called it “the hardest [class] to play.” So why bother?

It’s easy to play a morally gray, ethically amorphous character. It’s harder to play a consistently characterized and thought-out player. That’s what Gygax was trying to achieve here. He was encouraging players to adopt a real persona–a real person. And then to struggle within that persona. And in my mind, that really enriches not only the character, but the overall gameplay.

Don’t forget that you probably have an alignment too!

How many times have you had to make hard decisions that stretched or challenged your beliefs? Whether you consider yourself particularly spiritual or philosophical, we all have a worldview. We all have some kind of answer to what gives life purpose and meaning. It’s in the defining moments of life that we really have to stop and consider, “Wait. Can I justify this course of action? Or do I need to stop?” It’s these internal battles that shape our character most. Consider that, as you consider whether you want to introduce alignments more seriously into your roleplaying. How have these issues shaped you personally? And how could it shape your character and your adventuring group?

More poignantly, and perhaps more subversively, consider what it would be like to play a character whose alignment is quite unlike your own. What would it be like to consider that worldview more deeply–to challenge it–to test it–and even to try it out? Even if that’s a little too weird for you, I’ll get down to brass tacks. Here’s my challenge:

For the next four RPG sessions, encourage your group to adopt a hard stance on alignments. See how that would impact your sessions, your characters, and your overall gameplay. You may learn to love this old/new way of gaming. Or, if you don’t like it, house rule it or simply leave it behind. It won’t hurt my feelings! But in the end, I’ve found it to be an enriching part of AD&D and one that you should try as well.

In my GM sessions, I make sure everyone considers their characters alignments, flaws, bonds, etc. I refer to them as characters, and encourage them to act out their characters. If they do something that may be a bit different to what their alignment is, I say “This may be against [charactername]’s alignment. Why do you think [charactername] would do this action?”

I think alignments are great for solid role playing a character. It helps define actions. Defines personality. And drives improvisational story telling.

—-

Also, I love playing paladins and rangers. They’re my favorite type of classes to play. I also love playing war clerics.

I think 5e has ironed out some of the flaws and frustrations in paladins and clerics. Clerics are no longer armored nurses. Now they actually have some solid firepower. Paladins are pretty beastly, particularly once they’ve leveled some.

One of my favorite characters was a dwarf barbarian. My 5 year old son was playing as him. He was a chaotic good alignment. I used that as, when he’s just waltzing a round town he’s good, helpful, etc. His beard is well trimmed. He’s soft spoken for a dwarf. But the second he’s in battle and rages, his beast SPROINGS out, his eyes get bloodshot, and he gets loud and aggressive. Chaos embodiment. And my kids loved every moment when I voiced the character for them.

So yeah .. I like alignments. It also helps keep your group from being a bunch of murder hobos and ruining the fun. lol

I love how you redirect players. That’s a great statement:

“This may be against [charactername]’s alignment. Why do you think [charactername] would do this action?”

Keep up the good work.

The only part of alignments in AD&D that I didn’t like and never used was alignment languages. It just never made sense to me. After all, fascists don’t have some secret language that only a-holes understand.

Enforcing alignments, though, is part of the essence of the game, providing the PCs with boundaries of behavior, as well as some sense of how different NPCs and creatures will act and react.

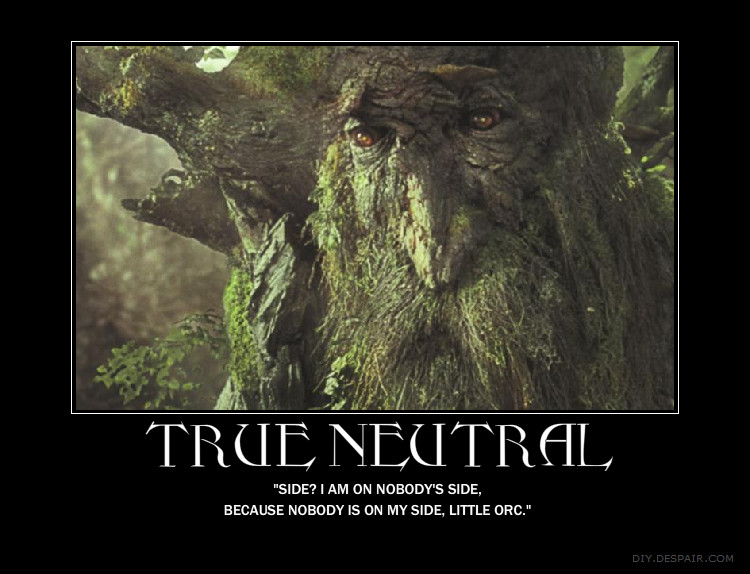

For example, elves, being typically chaotic good, while believing in life and freedom, tend to be less reliable in the grand scheme (think the elves leaving Middle Earth, rather than committing large numbers of troops to the war.

Another example is that the PCs know they can make deals with devils (lawful), and expect the conditions of the bargain will be upheld, while you should NEVER deal with demons. Demons (chaotic) will notoriously find a loophole in any deal.

Yeah, I don’t get alignment languages either. I wonder how many people actually used them.

Not me. Although I once toyed with the idea of making a setting with major factions that corresponded with the nine alignments, and giving them secret languages. Actually, the setting was going to normalize a bunch of things that were wonky about 1e. But at some point it just started to look silly.

Why silly? Just because it was so “meta”?

Well, maybe “silly” isn’t the word. It didn’t seem like a very fun world to play DnD in.

Imagine a society with ethically-based factions that are so paranoid they have secret languages that they WILL NOT teach them to anyone else. There are spells to determine what faction you belong to (Know Alignment), The factions cut across national and racial boundaries – a lawful elf would be isolated from the dominant faction of his society, as would a chaotic dwarf. These strictures are enforced by the gods themselves, who defrock paladins and refuse to grant spells to clerics who breach the factional code.

Now throw in societal pressures that are great enough to prevent people from training outside of their class, and if you ever violate them, you will never be permitted to train in your prior class again. And demihumans are forbidden from training above a certain level.

It would be one thing if the PCs could break that mold, but the whole point of the exercise was to justify PCs having to stay within it. That’s not DnD, its a game of Paranoia.