They call it a dungeon grind.

Not a dungeon frolic, a dungeon jaunt, or even a dungeon struggle.

It’s a grind. It’s a slog. An encounter-by-encounter, gear-grinding endeavor that makes even the most experienced player and GM tremble.

My second session of D&D as a GM was a dungeon freaking grind. Why? Well, I had a really big playmat, lots of new miniatures, and I wanted to use it all! But I learned very quickly that fight after fight after trap after fight can not only kill character, but also bore players. Is it possible to have a complex dungeon without boring the spit out of our players? I think you can. And I’m learning how to do it from Gary Gygax himself:

As you likely know, my home RPG group is 1-2 sessions from the end of T1: The Village of Hommlet. And, boy, it’s a grind. They search a room, find a trap. Search a room, get attacked, often to the point of unconsciousness or death. It’s not just the frequency of encounters, it’s the frequency of lethal encounters that are making it challenging. But with all that, my players don’t seem to be getting bored or frustrated with it. Why?

Good dungeon crawls use terrain to their advantage

All roads lead to Rome. But that doesn’t mean there’s only one way to get there. And Gygax applies that principle in spades.

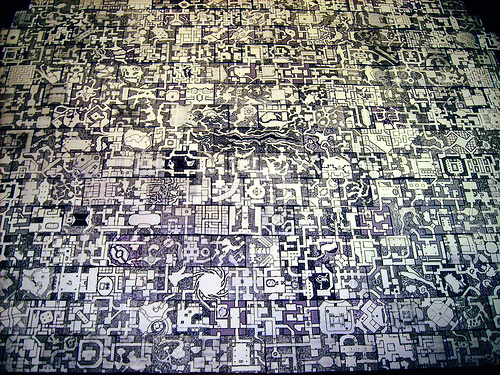

SPOILER ALERT: there’s a big bad evil guy [BBEG] at the end of The Village of Hommlet. And there are about a hundred different ways to get to him. A stairwell here, a long narrow hallway there, a secret door, and (oh!) a terrifying descent. But in the end, you’re going to the same place.

Such a variety of terrain, however, leaves your party feeling very uncomfortable. My players keep asking, “How big is this dungeon?” There’s a sense that there’s a lot going on that (a) we can’t fully explore and (b) we’re not sure we want to explore. It’s not a railroad. It’s a choose-your-own-adventure with built in tension and the same eventual end goal.

Beyond that, each of Gygax’s rooms has a personality and mind of its own. This module (at times) suffers for over-description. But when it strikes a chord, it strikes it well. Each room filled with the unexplained and degraded relics of yesteryear paint a bleak and unnerving picture for the players wandering through it. Of course, it helps too that the least scary room (a kitchen that smells like rotten food) has a beasty in it that almost sucked out the innards of our Fighter.

By varying the feel and tone of each room, it keeps the players engaged and on the end of their seats.

Good dungeon crawls present different battle challenges

One of the criticisms of AD&D 1e (that I’ve heard anyway) is the painfully unforgiving save rules. You know, “save vs. death,” “save vs. paralysis,” and the like. And let’s be honest: there’s no coming back from those rolls. You roll and the result stares you in the face. “Sorry, your character has perished.”

Last week, we faced our first “save vs. paralysis” roll. Holy mackerel! OK, so get this:

If the monster successfully attacks, the player must save vs. paralysis. If they fail, they are paralyzed for 3d4 rounds!

That, my friends, is a game-changer. By the end of the battle, two PCs and an NPC were paralyzed. The two remaining PCs were dragging them out of the room and hurriedly barricading themselves inside. The table talk got a little grim at one point. Statements like, “we’re doomed” and “what’s your next character going to be?” were floating around.

In the end with some creative teamwork and split-second judgment calls, the players made it through with everyone alive. What’s my point? We’re 90% of the way through this module and suddenly we’re seeing something new. The last battle was a horde of undead. That battle was a hack-and-slash, when-does-it-stop, we’re-all-going-to-die maelstrom! Before that, it was “us five” versus “that one big dude.” You see my point? Variety in battle and enemy style is just as important as terrain variety. It keeps the players wondering what could possibly be next, again upping the ante in terms of challenge and excitement.

But how can you apply these principles in your next dungeon crawl? Ask no further:

How you can build a good dungeon crawl like Gygax

First, you need to commit to a dungeon crawl. It can be a fearful commitment. You may be many sessions in the dank, dark dungeon depths. But you’ve got to make the choice. Get your BBEG holed up in there, get your map drawn out, and start the crawl.

Second, for each session take brief notes for three notable rooms. Make them colorful! Make them complicated. Include lots of obstacles for cover in battles and impediments in fleeing. Put in traps…or things that look like traps. Make some rooms too ordinary to trust. And then let them be ordinary. Listen: it doesn’t have to be overcomplicated. Sketch it out, make it fun, and move on. Choose which rooms they’ll be on your dungeon and roll with it.

Third, for each session be prepared for two combat encounters that are very different. You’ll have to gauge the speed of your players. But I’m learning that in AD&D 1e, my players can handle 1-2 dungeon fights each session. After that, they’ve got to go back to town for medical treatment. Gygax is ruthless…and I’m following his rules as closely as I humanly can. So if you’re designing your own dungeon crawl, look for what you think will be a reasonable number. Two will probably be good.

Fourth, don’t forget the spaces in-between. These are your hallways, your secret passageways, your mineshafts, and your tunnels. My players end up spending as much space in these as they are in rooms. Why? Because they’re nervous and preparing for what comes next. So jot down a note or two about these. And, honestly, reward curious players with secret doors, treasure, and what-not. Make it worth it to look for stuff in every nook and cranny.

I believe these principles will help you craft a dungeon crawl like Gary Gygax. A crawl, not a grind! You want your players to be engaged, excited, even nervous as they move through your dungeon…not wondering if it’s ever going to be over.

What other tips would you add? How do you make your dungeon crawls exciting? Sound off in the comments below:

Disclosure of Material Connection: the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive an affiliate commission. Regardless, I only recommend products or services I use personally and believe will add value to my readers. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.”

Another thing for a good dungeon crawl is not to make it a simple “get to this room, go to that room, dodge this trap, kill that badguy”. There has to be things in the crawl to allow the players to feel more invested other than get the loot and XP. Story telling elements help guide an otherwise slogging affair into a full adventure. Solid RP moments where elements of a character can shine bright in a dark cave.

The party has been delving into abandoned dwarven mines for a few sessions and you can feel the players becoming bored. They’re rolling, killing, checking for traps .. but it’s on automatic. So, looking at the backstories, you can add hints of a lost relative that may have come through. Or add an NPC that was trapped and now you have this extra character you’ve helped .. but in a few rooms you learn they’re not what they may have seemed.

Creating ways for the players appreciate that there is more to the dungeon than meets the eye will help the session fly, but also create memorable moments for everyone.

Just my thoughts. 🙂

Oh man, I love this tip! Not exactly Gygaxian, but it’s great nonetheless!

Nah, not very Gygaxian at all. But it’s more my style of game play anyway. It’s why my boys love D&D is because it’s not just hack n slash, but they get to tell a story beyond what they kill. Which leaves a bigger impression on them.

That’s my approach too, which has made Gygax an interesting challenge. Keep up the good work!

Gary Gygax and other early TSR writers were not always good about having explanations of WHY a creature was in a room. Take the time to understand or develop the reason they are there, especially if you are designing your own dungeons. Random giant toads in an underground room with no tunnel, lake, or something to explain it just feels like a stupid monster encounter to the players. Either swap out the encounter with one that makes more sense, or come up with creative reasons. Perhaps that toad was summoned by another party’s wizard or an evil wizard, who is now lying dead on the floor in that room. The summoned creature is still there without anyone controlling it. Monsters might be chained up as guardians to rooms so they are still dangerous but have limited reach. Or, the monster might have been attracted to the noise of combat, smell of blood, or even vibrations and thus broke into the dungeon on their own and now they are another menace to deal with.

If each room and encounter has a story based reason for existing, then the dungeon begins to come alive to the players. They feel immersed in an adventure with purpose, not just a series of random traps and combats.

I believe this is what you and I have discussed–the ecology of a module? It seems like there could be a way to design the ecology prior to the dungeon, so that you can use the beasties at your discretion from your established ecology, yes?

Wouldn’t you already have figured out what encounters will be in a dungeon anyway? If you’re creating the dungeon, for example, and you put something in there that naturally has no reason to be there, the GM better be ready to explain why. Because smart players will explore and investigate that phenomenon. If the module doesn’t make sense to the GM, he/she should adjust.

Dungeons aren’t random spawns points.

As I told a friend who GMed for me once, the module isn’t Scripture. Adjust it to fit your play style and to change it up to make sense.

Dungeon and Monster Ecology are developed so much more today then in the past. In 1st and 2nd Ed AD&D, that started being developed in the Dungeoneer’s and Wilderness Survival Guides and expanded on much more in Dragon magazine articles. Over the various editions, this has been touched on but 5th really delved into it. The 5th Ed D&D Monster Manual and the new Volo’s Guide to Monsters delve heavily into the ecology of monsters, how the environment around them is impacted, how various species interact, etc.

When I develop my own adventures, random encounter charts, and campaigns, I put a lot of thought into the history and purpose of every location, the environment of the surrounding area, and thus the impact on the potential ecology of the region. For pre-written modules, often old and sometimes new, I often have to retrofit those ideas and thoughts into the material, sometimes doing so on the fly.

That is one of the many reasons I encouraged GMs, storytellers, and writers to be very well read and researched. Over the years and to this day, I read books and watch videos on science, history, biographies, etc to expand my knowledge base. Good to do for your own personal growth, but highly recommended for creativity inspiration for storytelling and adventure writing.You never know when that reading and research will bring inspiration to a game.

This makes world creation seem a very challenging prospect for new gamers. How do you recommend world-builders (or dungeon-builders) start out with such a monumental task?

It doesn’t have have to be overwhelming. Start with the basics. Use common sense and what you learned in school. Put animals/monsters/villains in environments that make sense to them. When you are first learning, stick to the obvious. If it is a forest, use forest friendly creatures like animals, dryads, owlbears, etc. If it is underground, use undead or cave dwelling creatures like zombies, skeletons, kobolds, molds. Don’t try to stick an owlbear in your first dungeon unless you can come up with a reason why like perhaps they dug into the side of a hill to form a cave to hibernate in when they penetrated the walls of an old crypt. Think of the surprise to the players when they enter the crypt from a different entrance and stumble upon the owlbear hibernating in one of the rooms.

How about some examples:

Want to use an ancient crypt under a castle, then ask yourself some questions. Has it been accessed recently? If not, undead of various types makes sense since nothing would be living there. Molds, puddings, and lichens might work if you can find a food source for them. Now, use that same ancient crypt but have a clan of goblins stumble upon it and use it as a hide out to raid nearby villages. Now you could still have the undead in unexplored areas, but in used areas there could be goblins, their wolf mounts, a young otyugh they use to dispose waste, and perhaps some violet shriekers they planted for defense. You could even have a rust monster or carrion crawler that has been attracted to the scent of the goblins and is prowling about.

The new 5e D&D really helps wth this. The monster descriptions list common environments they can be found in. For more powerful monsters like dragons and liches, it lists other monsters that are often attracted to them and would be living nearby. These write ups really can help a new gamer build their worlds and dungeons.

I would add looping as another technique. For example, even with a dungeon as small as T1, there are two ways into the dungeon under the moathouse, and three ways out of it.

There are also two entrances to the second half of the dungeon. You can take the secret door/tunnel to the crypts, or the double secret door past the traps toward the humanoids. Note each of these is a different approach with a different feel – and the route to the crypts has a blood trail associated with it, which is the tiniest hint of what is to come.

This does a few things. Because some of the approaches are behind secret doors, it leads to uncertainty as to just how large the dungeon is, or whether the PCs have discovered the entire thing. As you alluded to, uncertainty is part of what keeps the players engaged.

Second, it the players become aware of both approaches, it gives them the option of alternate approaches to an area. For example, I just built a dungeon area with three approaches. One was through an ominous area with heaps of rotting vegetation (sleeping shambling mounds), the second was a “trick” door that opens if you agree to kiss the vile-looking magic mouth, and the third was behind a not-obvious secret door.

Having alternative approaches allows PCs to decide they don’t like the looks of something, and to try to find an alternate route. Moreover, each route should either have an obvious obstacle, or have some sort of clue associated with it, so that the decision to proceed or not is an informed one. This is important to a game where you want to encourage PCs to be selective about risk taking, and to avoid combat where possible.

This too is an excellent insight. Gives me a lot to think about.

The Dungeon is in The Underworld. You don’t have to explain the things in a logical way. Leave the ecology to the Wilderness and embrace the weird. The Dungeon is a fantastic weird enviroment. Go to look the encounter tables in DMG and you see all the assumptions and informations pop up the book.

Gygax don’t explain all to you is not a fall, but a feature.